The Adams Family and the Boylston Arms

Eugene Zieber observes, in Heraldry in America, that one area in which American heraldic custom has occasionally deviated from the British norms is in the use by some families of arms inherited in the female line, rather than strictly from father to son, as is the British rule. The most famous example of this practice is to be found in what some have called America’s most distinguished family, the Adamses of Braintree, Mass., who provided the Republic its second and sixth Presidents, John Adams and John Quincy Adams.

The English ancestors of the Adamses of Braintree were simple yeomen farmers in Somersetshire and, as far as anyone knows, were not armigerous. At any rate, none of the family seems to have used any kind of armorial bearings for their first 140 or so years in America. This did not deter John Adams from showing an interest in such things as a young man. On August 15, 1762, when he was 26, Adams wrote in his diary, "Yesterday I found in some of Crofts Books of Heraldry, a Coat of Arms given by Garter, King at Arms, about 130 Years ago, to one William Adams of the Middle Temple Counsellor at Law. It consists of Three Martlets sable, on a Bend between two O's--bezants." But Adams apparently understood that having the same last name did not entitle him to the arms, as there is no indication that he ever went beyond making a note of their existence.

By contrast, John Adams’ mother’s family, the Boylstons, were quite prominent in colonial Massachusetts, and in fact Dr. Peter Boylston, John Adams’ grandfather, had and used a seal with his family’s arms on it. Thus, when Susanna Boylston Adams passed this seal on to her eldest son, it seemed only natural for the future President to use it—and the coat of arms engraved on it—as his own. As a result, it is the shield and crest of the Boylstons that John Adams used when he needed armorial bearings to use in his diplomatic work in Europe. They appear printed on U.S. passports that he issued as the American minister to the Netherlands in 1782, for example, and the impression of his grandfather’s seal in red wax authenticates Adams’s signature on the Treaty of Paris of 1783. The same bearings were also used on a bookplate engraved that same year for his son, John Quincy Adams.

Boylston arms from passport issued by

John Adams as Minister to the

Netherlands

Source: "Adams Seals and Bookplates"

|

Impression from Boylston seal

used by John Adams on Treaty of

Paris, 1783

Source: "Adams Seals and Bookplates"

|

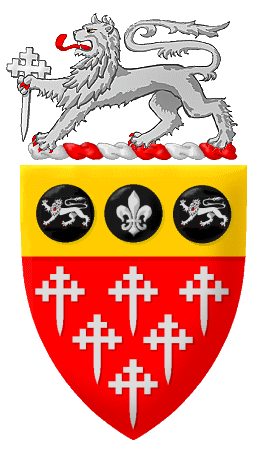

The Boylston arms as used by Adams up to this time were Gules six crosses crosslet fitchy 3, 2, and 1 Argent, on a chief Or three pellets. In ordinary terms, this describes a red shield with six silver crosses as depicted above, and on a gold field at the top of the shield three black balls. According to a posting by Don Stone in the rec.heraldry newsgroup on April 24, 1998, citing A. W. Hughes Clarke’s London Pedigrees and Coats of Arms, these arms were confirmed in the English heralds’ 1664 visitation of London to a Thomas Boylston, citizen and cooper of London, son of Henry Boylston of Lichfield, Staffordshire. It was another Thomas Boylston, the descendant of a family from Derbyshire, who had emigrated to Boston in 1635 to found the Massachusetts line of the family. The only difference between the arms as confirmed in 1664 and those used in Massachusetts was that the lion in the crest in the English version was ermine—white sprinkled with black “tails”—while that used by the American Boylstons was plain white or silver (argent). As the Massachusetts Boylstons and their English cousins seem to have been in regular contact, and as Staffordshire and Derbyshire are neighboring counties, it seems reasonable to suppose that Thomas Boylston of Brookline and Thomas Boylston of London shared a common ancestor from whom these arms were inherited.

John Adams bookplate, 1783,

with differenced arms of Boylston.

Source: "Adams Seals and Bookplates"

In 1783, John Adams ordered a bookplate engraved in London in which he introduced a change to the original Boylston arms. To commemorate his own diplomatic service, he charged the outer two pellets in the chief of the arms with lions (the heraldic animal of Great Britain and the Netherlands) and the center one with a fleur-de-lys (the heraldic symbol of France). These are the arms shown at the top of the page. In addition, he had the shield surrounded by a strap and buckle, often wrongly called a “Garter,” inscribed with the motto Libertatem amicitiam retinebis et fidem, a rearrangement of a phrase from the Annals of Tacitus meaning “Hold fast to liberty, friendship, and faith.” The whole achievement was surrounded by an oval of thirteen white stars. Two years later, in 1785, Adams had a new seal cut exactly duplicating the design on the bookplate.

As avid a user of these arms as he had been, however, John Adams was clearly uneasy about how personal heraldry might be perceived by the public as a throwback to monarchical rule. Nowhere are these qualms more clearly seen than in correspondence between Adams and his wife Abigail in the months leading up to his inauguration as President in early 1797. Adams had been stung by the bitter campaign invective of 1796, which had portrayed him—the man who had been perhaps the most prominent advocate of American independence in 1776—as a pompous would-be aristocrat and even a pro-British monarchist. Thus he was determined not to give his critics additional ammunition through his personal style, one of his key concerns being that the carriage used at the inaugural ceremony be sufficiently dignified without being open to accusations of ostentation. After several exchanges of letters with Abigail as to whether her carriage, which had the family's armorial bearings emblazoned on it as was customary, might be satisfactory, Adams wrote to her on February 2, 1797, to close the discussion:

I had before bespoke a new Chariot here [in Philadelphia], and it is or will be ready: so that there is an End of all further Enquiries about Carriages. I hope as soon as the Point is legally settled you will have your Coach new Painted and all the Arms totally obliterated. It would be a folly to excite popular feelings and vulgar Insolence for nothing.

1.1 The Pine Tree, Deer, and Fish

Like Thomas Jefferson, who did not mention having been President of the United States on the epitaph he wrote for his own tomb, John Adams took his greatest pride in achievements of which many modern Americans are not well aware. One of these was having secured, in the negotiations that concluded the Revolutionary War, British agreement that the western border of the newly independent United States would extend all the way to the Mississippi River and that “the people of the United States shall continue to enjoy unmolested the right to take fish of every kind on the Grand Bank and on all the other banks of Newfoundland, also in the Gulf of St. Lawrence and at all other places in the sea, where the inhabitants of both countries used at any time heretofore to fish.” To celebrate this achievement, Adams had another seal cut in 1783 with a device of his own design, depicting a stag next to a pine tree, beneath which a codfish swims on a pattern of waves. Above these emblems, which are set on an oval background, was an arc of 13 stars. In 1816, after his son John Quincy Adams successfully secured the reiteration of these rights in the Treaty of Ghent that ended the War of 1812, the elder Adams had a revised version of this seal engraved, adding at the bottom a scroll inscribed with a quotation from Horace: Piscemur venemur ut olim—“Let us fish and hunt as we were wont to do.”

Seal designed by John Adams, 1783,

as modified 1816

Source: "Adams Seals and Bookplates"

↑ Back to Top

John Quincy Adams: Ambivalence about Traditional Heraldry

In his early diplomatic career, John Quincy Adams used his father’s 1785 seal with the differenced version of the Boylston arms, and he used the same arms on a bookplate, but with the ring of stars omitted and the motto shortened and rearranged to Fidem libertatem amicitiam—“Faith, liberty, friendship." In 1816, however, he had a new seal cut in London based loosely on the national coat of arms. An entry in his diary for January 26, 1819, explains his reasoning:

… as there is no heraldry in the United States, seals-at-arms are an absurdity, used by a public officer of this country. I have used a seal-at-arms in Europe, as my father had done before me. But so far as there is any significancy in such seals, they are utterly inconsistent with our republican institutions. Arms are emblematical hereditary titles of honor, conferred by monarchs as badges of nobility or of gentility, and are incompatible with that equality which is the fundamental principle of our Government. I have, therefore, determined never more to use my seal-at-arms (which are not the Adams, but the Boylston arms) to any public instrument.

The new device consisted of an American eagle displayed with wings inverted, charged on the breast with a lyre bearing the motto Nunc sidera ducit—“Now it leads the stars”—and the stars of the constellation Vultur et Lyra. It apparently did not occur to the younger Adams that neither his father, nor Benjamin Franklin, nor John Jay seemed to consider the armorial seals they applied in signing the Treaty of Paris as incompatible with the fundamental principles of republican government, and he may not have known that George Washington himself had explicitly rejected that view. One wonders whether, as the younger Adams contemplated a career in electoral politics, he might have shared his father's qualms about popular reaction to the perceived snobbishness of a traditional coat of arms being used in public.

Eagle and Lyre Device

adopted by John Quincy Adams, 1816

Source: The Eagle and the Shield

|

Bookplate of John Quincy

Adams, circa 1830

Source: "Adams Seals and Bookplates"

|

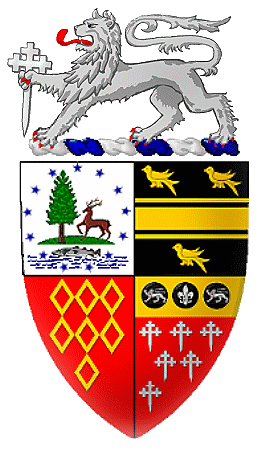

For personal, as opposed to official, purposes, John Quincy Adams was clearly less averse to heraldic tradition. In 1831, he wrote a letter to his son Charles Francis Adams explaining the design of an armorial bookplate he had designed. He prefaced the discussion by asserting that since the separation from Great Britain, “as heraldry forms no part of our institutions, the use of Seals at Arms serves no purpose but to retain the memory of the families in the Old World, from which the individuals still bearing the arms are descended.” Accordingly, he had devised the new coat of arms shown on his last bookplate. The shield was divided quarterly. In the first quarter was an adaptation of the deer, pine, and fish device his father had adopted to commemorate his achievements in the negotiations with Britain. This quarter evidently represented the Adams family itself. Except for the stars, which are hatched with horizontal lines indicating the color blue, the bookplate gives no indication of tinctures for this quarter, which would suggest that it should be shown with the charges in their natural colors against a silver or white field. The second quarter represents the family of John Quincy’s mother Abigail Smith Adams, and the third quarter Abigail’s maternal line of Quincy. Finally, in the fourth quarter, are the familiar Boylston arms used before. The crest is also that from the Boylston arms, and the motto is again the passage from Tacitus, this time in the most common order, Fidem libertatem amicitiam retinebis.

2.1 The Oak Leaf Seal

In about 1838, John Quincy Adams had yet another seal cut, this one simply an acorn between two leaves of white oak above a scroll inscribed Alteri seculo, “Another age.” The motto derives from a passage in Cicero’s Tusculan Disputations: Serit arbores quœ alteri seculo prosint—"He plants trees for the benefit of another age.” It was this emblem that was carved on the marble memorial to John Quincy Adams and his wife Louisa at the United First Parish Church in Quincy, Mass., and on the tombstone of their son Charles Francis. Of all the Adams devices, it is this one that has lived on into institutional heraldry in the 21st century as the basis for the coat of arms of Adams House, one of the undergraduate residential houses at Harvard University, Or five sprigs of oak acorned in saltire Gules.

The Oak Leaf Seal

|

Arms of Adams House,

Harvard

|

↑ Back to Top

The Purported Arms of Henry Adams of Braintree

A number of standard American heraldic sources, including Crozier's General Armory and Matthews' American Armoury and Blue Book, ascribe to one Henry Adams of Braintree, Mass., the arms Argent on a cross Gules five mullets Or, with the crest, Out of a ducal coronet a demi-lion rampant affronty Gules. As this Henry Adams, who emigrated to Massachusetts from Somerset in about 1639, was the great-great-grandfather of John Adams, it may be supposed that this, rather than the Boylston arms, should have been the coat used by the two Presidents. But, as already stated, there is no evidence that Henry or any other of the Massachusetts Adamses ever used these arms before the late 19th century. The arms originally belonged to Sir John ap Adam, apparently a Welsh knight in the service of King Edward I of England, and are shown under his name in the roll of arms of Edward’s knights at the battle of Falkirk in 1298. Six centuries later they appear in Burke’s General Armory of England, Scotland and Wales(1884) as pertaining to several families of Adamses in Pembroke, Carmarthen, and London. Their purported connection to the Adamses of Massachusetts would seem to arise from a pedigree of Henry the emigrant published in the New England Historic Genealogical Register in 1853. This article traced Henry’s lineage back to the brother of a Nicholas Adams of Devonshire, who in turn was traced back in the heralds’ 1564 visitation of Devonshire to the knight who had born the arms at Falkirk. Unfortunately, a later Adams genealogist found that the connection between Henry and the Devonshire family was apocryphal, and moreover that the direct male line of Sir John ap Adam died out in the 15th century. These arms therefore have no historical connection with the two Adams Presidents or their family.

Nevertheless, the Dobrée Museum in Nantes, France has in its collections a wax impression, roughly 20 mm in diameter, clearly showing the arms of John ap Adam, which it attributes to John Adams, 2° Président des Etats-Unis. The museum's website does not mention the provenance of this seal. If it was indeed used by John Adams, it is surprising that Henry Adams did not mention it in his book about the family seals, since he was so manifestly uncomfortable with his ancestor's use of the Boylston arms. Clearly more research needs to be done.

Seal impression attributed to John Adams

Source: Dobrée Museum, Nantes

↑ Back to Top

Sources

- Adams, Henry. John Adams's Book: Being Notes on a Record of the Births, Marriages and Deaths of Three Generations of the Adams Family, 1734-1807. Boston: Athenaeum, 1934; online version at Ancestry.com

- Adams, John, and Abigail. Correspondence between John and Abigail Adams. Adams Electronic Archive, Massachusetts Historical Society

- Adams, Henry. “The Seals and Book-Plates of the Adams Family, 1783-1905,” in A Catalogue of the Books of John Quincy Adams Deposited in the Boston Athenaeum. Boston: Athenaeum, 1938.

- Bartlett, J. Gardner. Henry Adams of Somersetshire, England, and Braintree, Mass.: His English Ancestry and Some of His Descendants. New York: 1927; online version at Ancestry.com

- Bemis, Samuel Flagg. John Quincy Adams and the Foundations of American Foreign Policy. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1949.

- Bolton, Charles Knowles. Bolton's American Armory. Boston: F. W. Faxon, 1927.

- Musée départementale Dobrée, Nantes France

- Patterson, Richard S., and Dougall Richardson. The Eagle and the Shield: A History of the Great Seal of the United States. Department of State Publication 8900. Washington: Government Printing Office, 1976.

- Peabody, James Bishop. John Adams: A Biography in His Own Words. New York: Newsweek, 1973.

- Timms, Brian. “European Rolls of Arms of the Thirteenth Century.” Studies in Heraldry.

- Zieber, Eugene. Heraldry in America. 1895; rpt. New York: Greenwich House, 1984.

↑ Back to Top