The Arms of the USA—Development of the Design

by Joseph McMillan

The First Committee (1776)

The definitive history of the great seal of the United States, Richard S. Patterson and Richardson Dougall’s The Eagle and the Shield (1978) explains how, on the most historic day in American history, the three men most directly responsible for the just-signed Declaration of Independence found themselves entrusted with a new assignment: “On July 4 [1776], just before completing its business for the day, the Continental Congress approved the following resolution: ‘Resolved, That Dr. Franklin, Mr. J. Adams and Mr. Jefferson, be a committee, to bring in a device for a seal for the United States of America.’" Patterson and Dougall go on to observe that:

Although the committee to bring in a Great Seal device boasted three of the ablest minds in the thirteen United States, they were peculiarly unqualified to suggest or compose a suitable design. Wisely, therefore, they sought help. In Philadelphia at the time was a remarkable man, Pierre Eugène Du Simitière. This man, who had many skills and interests, was a talented “drawer” and portrait artist, he knew something of heraldry, and he had experience in designing seals.

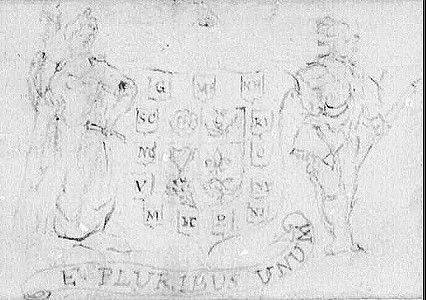

For the next six weeks, Franklin, Adams, Jefferson, and Du Simitière consulted, and each of them put forward his own design for the seal. Franklin proposed a biblical scene featuring Moses parting the Red Sea; Adams the mythological judgment of Hercules. Jefferson suggested a two-sided pendant seal with the children of Israel in the wilderness on one side and the leaders of the Saxon settlement in England, Hengist and Horsa, on the other. Jefferson soon withdrew his proposal in favor of a slightly modified version of Franklin’s. Then, on August 13, Adams visited Du Simitière to look at the expert’s ideas, which, unlike the others’, were along more conventional heraldic lines. The original sketch, along with the designer’s description, have been preserved among Thomas Jefferson’s papers in the Library of Congress.

On August 20, the committee reported to the Congress its recommendation for the design of a two-sided pendant seal. The committee opened its report with the statement that, “The great Seal shd on one side have the Arms of the United States of America.” It then provided the following blazon, very slightly modified from Du Simitière’s proposal of the week before:

The Shield has six Quarters, parti one, coupé two. The 1st Or, a Rose enammelled gules & argent, for England: the 2d Argent, a Thistle proper, for Scotland: the 3d Verd, a Harp Or, for Ireland the 4th Azure, a Flower de Luce Or for France the 5th Or the Imperial Eagle Sable, for Germany: and the 6th Or the Belgic Lion Gules for Holland pointing out the Countries from which these States have been peopled. The Shield within a Border Gules entoire of thirteen Scutcheons Argent linked together by a Chain Or, each charged with initial Letters Sable, as follows 1st NH. 2d M.B. 3d RI. 4th C. 5th NY. 6th NJ. 7th P. 8th DC. 9. M. 10th V. 11th NC. 12th SC. 13 G. for each of the thirteen independent States of America.

Supporters, dexter, the Goddess Liberty in a corselet of armour alluding to the present Times, holding in her right Hand the Spear & Cap and with her left supporting the Shield of the States; sinister, the Goddess Justice bearing a Sword in her right hand, and in her left a balance.

Crest The Eye of Providence in a radiant Triangle whose Glory extends over the Shield and beyond the Figures

Motto E PLURIBUS UNUM

The only significant changes between this and Du Simitière’s previous design were the deletion of an anchor upon which Liberty’s left hand had previously rested, and the substitution of Justice for an American soldier holding a rifle and a tomahawk. For a reverse, the committee recommended Franklin’s non-heraldic scene of Moses parting the Red Sea with the motto “Rebellion to Tyrants is Obedience to God.”

Unfortunately, Du Simitière’s design was excessively complicated. Strangely enough, it prefigured a shortcoming in many modern personal arms in the United States, sometimes derided as “Lucky Charms heraldry,” a desire to represent a multitude of ethnic origins through an assortment of hackneyed national symbols—a rose for England, a fleur-de-lis for France, a thistle for Scotland, and so on. Sensibly enough, Congress responded by ordering the report “To lie on the table.” For all practical purposes, that ended the work of the first committee.

The Second Committee (1780)

submitted by the second committee

Source: National Archives

The report continued to “lie on the table” for more than three and a half years. It was not until March 25, 1780, that Congress named a new committee--consisting of James Lovell of Massachusetts, John Morin Scott of New York, and William Churchill Houston of New Jersey--to take up where the first committee had left off. Like the first committee, the second turned for assistance to someone with a knowledge of heraldry, a former member of Congress named Francis Hopkinson. Hopkinson, who is generally credited with the design of the American flag (to the extent that it can be credited to any single individual), seems to have been the only person associated with the second committee who made any tangible contributions to the process. He developed two proposals, each with an obverse and a reverse. The two obverses were similar, each consisting of a proposed coat of arms for the United States with shield, crest, and supporters. The first shield had a field of 15 (probably a drawing error) diagonal white and red stripes, while the second has a diagonal band of 13 white and red stripes on a blue field. Both have the same crest, a constellation of 13 six-pointed stars. The first shows the stars placed above a helmet, while the second has them directly above the shield. Both versions have supporters symbolizing war to dexter and peace to sinister, but the original figure representing war, an Indian holding a bow and arrow, is replaced in the second draft by what is evidently supposed to be a Roman soldier with a drawn sword. Both have mottoes that also refer to war and peace, the first being Bello vel Pace Paratus (“Prepared for war or peace”) and the second simply Bello vel Paci (“War or peace”).

The committee submitted Hopkinson’s second design to Congress on May 10, 1780. As printed in the Journals of the Continental Congress for May 17, the day the proposal was considered, the committee’s proposal for “the Arms of the United States” was blazoned:

The Shield charged on the Field Azure with 13 diagonal stripes alternate rouge and argent— Supporters; dexter, a Warriour holding a Sword; sinister, a Figure representing Peace bearing an Olive Branch— The Crest— a radiant Constellation of 13 Stars— The motto, Bello vel Paci.

Once again, Congress was not taken with the proposed design. The matter was referred back to the committee, but the committee took no further action. With this, work on the arms and seal again came to a stop.

The Third Committee (1782)

Again a prolonged interlude elapsed before the matter of the seal and arms were taken up once more. It was not until May 4, 1782, that Congress designated Arthur Middleton of South Carolina, Elias Boudinot of New Jersey, and John Rutledge of South Carolina as yet a third committee on a “Device for a Seal of the U.S.” (Arthur Lee of Virginia later joined the work of the committee in place of Rutledge, although he was never officially appointed to it.) Following the precedent established by the first two committees, the third also sought expert help, this time from yet another Philadelphian with an interest in heraldry, the lawyer William Barton.

Barton responded by producing two proposed “devices for an Armorial Atchievement, for the Great Seal of the United States of America, in Congress assembled; agreeable to the Rules of Heraldry.” His blazon of the first was:

Arms.

Barry of thirteen Pieces, Argent & Gules; on a Canton Azure, as many stars disposed in a Circle, of the first: a Pale, Or, surmounted of another, of the third; charged, in Chief, with an Eye surrounded with a Glory, proper; and, in the Fess-point, an Eagle displayed, on the Summit of a Doric Column which rests on the Base of the Escutcheon, both as the Stars.

Crest.

On a Helmet of burnished Gold damasked, grated with six Bars, and surmounted of a Cap of Dignity, Gules, turned up Ermine, a Cock armed with Gaffs, proper.

Supporters.

On the dexter Side: The Genius of America (represented by a Maiden with loose Auburn Tresses, having on her Head a radiated Crown, Of Gold, encircled with a Sky-blue Fillet spangled with Silver Stars; and clothed in a long loose, white Garment, bordered with Green: from her right Shoulder to her left Side, a Scarf semé of Stars, the Tinctures thereof the same as in the Canton; and round her Waist a purple Girdle fringed or; embroidered, Argent, with the Word “Virtue”:)—resting her interior Hand on the Escutcheon; and holding in the other the proper Standard of the United States, having a Dove, argent, perched on the Top of it.

On the sinister side: a Man in complete Armour; his Sword-belt, Azure, fringed with Gold; his Helmet encircled with a Wreath of Laurel; and crested with one white & two blue Plumes: supporting with his dexter Hand the Escutcheon, and holding, in the exterior, a Lance with the Point sanguinated; and upon it a Banner displayed, Vert,--in the Fess-point an Harp, or, stringed with Silver, between a Star in Chief, two Fleurs-de-lis in Fess, and a pair of Swords in Saltier, in Base, all Argent. The Tenants of the Escutcheon stand on a Scroll, on which is the following Motto—

“Deo favente”—

which alludes to the Eye in the Arms, meant for the Eye of Providence.

Over the Crest, in a Scroll, this Motto—

“Virtus sola invicta”—

which requires no Comment.

Accompanying the blazon was Barton’s explanation of the design. The thirteen bars in the field, as well as the stars in the canton, represented the thirteen states, the stars specifically denoting a new constellation, a new empire among the empires of the world. The stars were in a circle to represent the perpetual union of the states. The eagle, a symbol of power and authority, represented Congress, placed atop a column signifying a well-planned government. The eagle and pillar were placed on a pale surmounting the thirteen bars as an expression of the sovereignty of the United States. The gold, six-barred helmet is, according to European heraldic custom, emblematic of a sovereign, while Barton explained the cap of maintenance as a “token of Freedom & Excellency.” The cock in the crest symbolized vigilance and fortitude.

Everything in Barton’s design seems to have been symbolic of something. Liberty’s dress, white edged with green, was said to represent innocence and youth. The purple girdle and golden crown were for sovereignty; the word “Virtue” was inscribed on the girdle to express that that “should be her principal Ornament,” while the crown was radiant to show that “no Earthly Crown shall rule her.” The dove at the top of the flagstaff was for the mildness and lenity of the American government. On the sinister side of the shield, the knight with his bloody lance represented the military side of the American government in defense of its rights. The blue belt and plumes were for the country itself, the white plume a compliment to America’s French allies. The green of the knight’s banner was for youth and vigor; the harp for the states acting in harmony, the star for America, the fleurs-de-lis again for French support of the American Revolution, and the crossed swords for a state of war.

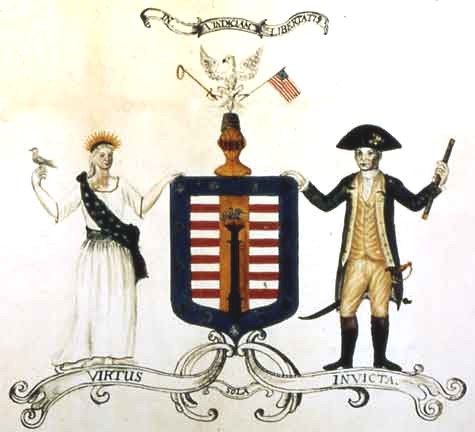

No drawing of this complex composition seems to have survived, but the National Archives holds a color painting made by Barton of a second version, equally complicated, which he blazoned as follows:

Arms.

Barry of thirteen pieces, Argent & Gules; on a pale, Or, a Pillar of the Doric Order, Vert, reaching from the Base of the Escutcheon to the Honor point; and, from the Summitt thereof, a Phœnix in Flames with Wings expanded, proper: the whole within a Border, Azure, charged with As many Stars as pieces barways, of the first.

Crest.

On an Helmet of Burnished Gold, damasked, grated with six Bars, a Cap of Liberty, Vert; with an Eagle displayed, Argent, thereon: holding in his dexter Talon a Sword, Or, having a Wreath of Laurel suspended from the point; and, in the sinister, the Ensign of the United States, proper.

Supporters.

On the dexter side, the Genius of the American Confœderated Republic: represented by a Maiden, with flowing Auburn Tresses; clad in a long loose, white Garment, bordered with Green; having a Sky blue Scarf, charged with Stars as in the Arms, reaching across her Waist from her right Shoulder to her left Side; and, on her head a radiated Crown of Gold, encircled with an Azure Fillet spangled with Silver Stars: round her Waist a purple Girdle, embroidered with the Word “Virtus”, in Silver[,] A Dove, proper, perched on her dexter Hand.

On the sinister side, an American Warrior; clad in an uniform Coat, of blue faced with Buff, and in his Hat a Cockade of black & white Ribbons: in his left Hand, a Baton Azure, semé of Stars Argent.

Motto, over the Crest— “In Viniciam Libertatis”—

Motto, under the Arms— “Virtus sola invicta”.

Most of the symbolism was the same as in the previous version. Barton said the phoenix symbolized the “expiring Liberty of Britain, revived by her Descendants in America.”

The committee reported Barton’s second design to Congress on May 9, 1782. It seems to have been no better received than any of the previous efforts. The following month, on June 13, Congress finally took the matter out of the hands of committees and put it into those of its able secretary, Charles Thomson. Thomson had already been involved on the margins of the third committee’s work and would soon finish the job to Congress’s satisfaction.

Thomson and Barton Finish the Job (June 1782)

Within less than a week, Thomson had produced a radically different conception that set the basic pattern for the final coat of arms of the United States.

On a field, _____ Chevrons composed of seven pieces on one side & six on the other, joined together at the top in such wise that each of the six bears against or is supported by & supports two of the opposite side the pieces of the chevrons on each side alternate red & white. The shield borne on the breast of an American Eagle on the wing & rising proper. In the dexter talon of the Eagle an Olive branch & in the sinister a bundle of Arrows. Over the head of the Eagle a Constellation of Stars surrounded with bright rays and at a little distance clouds.

In the bill of the Eagle a scroll with these words E pluribus unum.

A drawing of this design, evidently by Thomson’s hand, shows that, although he failed to mention it in the blazon, the field of the shield was intended to be blue.

Source: National Archives

As can be seen from the illustration, the arms were now recognizably in what would be their final form, except for the most important part: the shield. The basic idea of a blue area with white and red stripes, first developed by Hopkinson and presumably derived from the design of the national flag, seems to have been settled. But while Thomson’s idea of arranging the stripes comprising the chevron to symbolize the states all supporting and being supported by one another was conceptually clever, the mathematics simply worked out to create a very awkward appearance.

Thomson took his effort to Barton, possibly just so the blazon could be put into heraldic language or possibly to get his thoughts on the design itself. Whatever the purpose, Barton took Thomson’s draft and turned it into what we now know as the arms of the United States. On June 19, he completed the blazon and the redesign of the shield. Hopkinson had tried thirteen white and red stripes bendwise (diagonally); Barton’s work with the third committee had tried them fesswise(horizontally); and Thomson had tried them chevronwise (in an inverted V). The only obvious untried option was to arrange them palewise (vertically), which is what Barton did, with the blue now appearing as a chief across the upper part of the shield. Beyond that, and drafting the blazon that was approved by Congressthe following day, Barton’s only amendments to Thomson’s design were to present the eagle as displayed, with its wings spread and elevated, instead of rising as it had appeared in Thomson’s sketch, and to specify the arrows in the eagle’s left claw as 13 in number. After nearly six years, the arms of the United States of America were complete.

The above is largely drawn from the official history of the great seal of the United States, Richard S. Patterson and Richardson Dougall, The Eagle and the Shield: A History of the Great Seal of the United States, Department of State Publication 8900 (Washington: Department of State, 1978).